Three Fathers

(Chiam Fialko, Sol Falk and Fred Falk)

This family story begins with a Jewish peasant who lived in a village outside of Minsk over a hundred years ago. His name was Chaim Fialko and he supported his family by working as a blacksmith. Little else is known about him apart from a story that has been passed down through his descendants.

One evening as Chaim and his son, Solomon, walked home from the blacksmith’s shop they noticed a farmer burying money. As strange as it may sound, it wasn’t unusual during this time for Russian land owners/farmers to bury their money. Banks weren’t readily available and if they kept their money in their homes it could be stolen.

Chaim stopped on the road and told Solomon they needed to go back and speak to the farmer. They had an obligation to tell him they’d witnessed where he’d buried his money. The blacksmith and his son went to the farmer, told him what they’d seen, and then left so the appreciative man could relocate his money.

Chaim died young. He was gone before Solomon was ten years old, but the walk home in which they’d spoken to the farmer was never forgotten. Solomon carried the story with him for the rest of his life.

By the time Solomon was nineteen the Russian army was conscripting peasants to be cannon fodder in the First World War. To escape this fate and to find work Solomon Fialko became the more American-sounding, Sol Falk and followed an older brother who’d emigrated to Sioux City, Iowa and opened a junkyard. Sol went to work for his brother and, though he would always retain his Russian accent, began to learn English.

After a few years of working for his brother, Sol opened his own small shop in the Sioux City suburb of Leeds where he patched tires. He was ambitious and five years later opened his own junkyard, Reliable Auto Salvage, on the west side of Sioux City.

There are black and white photos of Sol’s first junkyard. The hulks of partially dismantled Model A’s and Model T’s stand in mud, hundreds of wooden automobile wheels lean against wooden fences and innumerable rear suspensions, dismantled transmissions and other reclaimed parts are stacked as high as a man’s shoulders.

In one photo Sol is emerging from his windowless shack (an improvised-looking tin chimney makes one wonder what the working conditions must have been during the Midwestern winters) while two men wait outside. One man is standing with his hands in his pockets while another sits on an upended wooden crate, leaning forward on his elbows. The image is reminiscent of Dorthea Lange’s Depression-era photos and despite the prevailing austerity of the time, Sol, who always wanted to appear professional, is wearing a suit and tie.

In the early-1930’s Sol had watched the steady climb in the price of scrap metal and saw an opportunity to expand his business. For a year he accumulated all the scrap metal he could, and borrowed five hundred dollars from his bank to purchase more iron, steel, tin and junked car parts. Sol found a buyer, hired a crew to load the scrap metal and had an open train car placed on the railroad spur next to his junkyard. Everything was set as the date for delivering the metal approached.

Then the bottom dropped out of the scrap metal market and everything Sol had accumulated was rendered almost worthless. Any potential profit was wiped out. Sol could no longer afford the crew to load the train and defaulting on the loan would ruin him financially.

It was devastating, but Sol had always maintained his word was his bond, so on a hot summer’s day he loaded the scrap metal by himself. He used a pitchfork when he could to pitch the parts and pieces of metal into the train car. The hard labor tore muscles in Sol’s arms, back and shoulders which would never fully heal, but the metal was delivered and Sol received enough money to pay back his loan. The ordeal took an emotional, physical and financial toll on Sol, but he’d kept his word.

In the following decade Sol became a US citizen and married a pretty Latvian immigrant named Lucile Palin. Lucile gave Sol two sons and became his partner in the automotive parts store which he had built a half block east of his junkyard. Lucile worked countless hours alongside Sol and their store eventually expanded into a gas station and a repair shop. Sol, who would never personally own a new car, also bought, sold and traded used cars and trucks. With just a 6th grade education, Sol had lifted his young family into the middle class and achieved the American dream.

Unfortunately, there were more setbacks. After World War II, Sol was pushed out of a second, more lucrative business by an unscrupulous investor which, like the scrap metal venture, was a profound disappointment for him. Later, he also lost a second junkyard in a flash flood. He went home to lunch one afternoon and when he came back his junkyard was under ten feet of water.

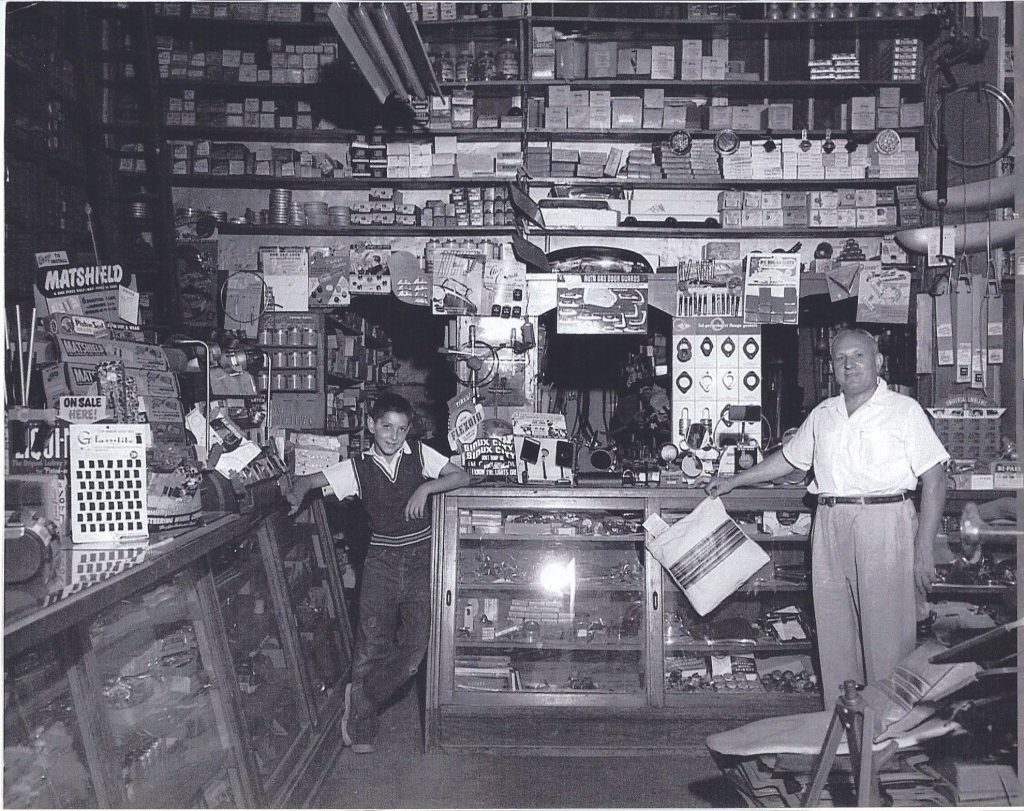

By the 1950’s Sol and Lucile’s youngest son, Fred, was working with them in their store. He swept the floors, set-up displays, cleaned shelves and eventually became knowledgeable enough about car and truck parts to wait on customers. Customers got a kick out of having a kid help them and Fred liked the affirmations he received from his parents for working hard and helping them in the store.

During these formative years, Fred listened to his father’s old family stories. He learned something about honesty and magnanimity from the story of his grandfather and the farmer and something about integrity, disappointment and perseverance from the story of his father and the scrap metal venture. Fred, like Sol, would never forget the stories.

In 1966 Fred came home on spring break from the University of Iowa where he was in his last year of college. His mother woke him one morning and told him his father wasn’t well and that he needed to drive him to the hospital. Fred and Sol rode in silence and Fred knew his father was afraid when he reached for his hand. Sol had said that no one ever wanted to go to the hospital in Minsk because those who did often didn’t come out alive. Unfortunately for Sol and his family, the same thing happened in Sioux City. Sol died of a heart attack in the hospital while awaiting medical attention.

Fred stayed in Sioux City to help his mom run the store. Lucile continued to order parts, keep the books and operate the cash register while Fred took over for his father and became the store’s manager.

A year later a salesman from Los Angeles convinced Fred to order eight, expensive chrome car wheels. When the wheels arrived, Fred began to set up a display for them, but before he could finish they were sold. Fred ordered eight more and the salesman sent him forty. Fred was angry, but the wheels sold in just two days. Fred then ordered forty and the salesman sent him a hundred and twenty. Fred couldn’t believe the audacity of the salesman, but the chrome wheels sold in a week. Fred’s timing was better than his father’s and the era of the muscle car had arrived. He went to his bank and after his mother cosigned for the loan, received five thousand dollars to buy more high-performance car parts.

Over the next three decades the business which Sol had begun grew exponentially. Fred eventually owned fourteen distribution centers, some as large as a hundred thousand square feet, and had, at his peak, almost four hundred employees. Fred knew his mother was proud of him, but wished his father could have shared their accomplishments. It was bittersweet for Fred and he hoped through his hard work he’d vindicated some of his father’s earlier setbacks.

Lucile passed away in 1999 and Fred is now retired and living in a leafy suburb of Minneapolis. He isn’t ostentatious, has a great sense of humor, and likes ethnic food, progressive politics and the Minnesota Timberwolves. Fred also has a beloved granddaughter and three grown children who are making their own forays into business.

Sometime in the early-1950’s, Sol traveled to Chicago and purchased a cream-colored, ’49 Buick Convertible. He towed the Buick back to Sioux City and ordered green plaid canvas to replace the Buick’s torn upholstery and top. After the car was refurbished Lucile considered the green plaid to be a bit much, but Sol loved it. No one in Sioux City owned anything like it and anyone living there at that time would soon recognize Sol when he was coming down the road.

A large, porcelain cookie jar which is a replica of Sol’s ’49 Buick sits in Fred’s living room. It is a reminder of a father who sacrificed for his family and who, by anyone’s estimation, was a success.